A Sprinkle of Dust: A Mother’s Struggle with Loss and Healing is a powerful memoir about a close-knit Arab-American family’s attempt to sustain a young man battling cancer and to recover after his death. Author Mary Saad Assel, a retired professor of English at Henry Ford College, has had an eventful life. Living in Lebanon, Senegal, and the United States, she has faced many crises with determination, strength, and love. Saad Assel writes in the prologue, “I was a wife at fifteen, a mother at sixteen, a widow at thirty-five, and heartbroken by the loss of my son at fifty” from a “terminal brain tumor” (p. xiii). This book “describes how I struggled to find hope and meaning in a challenging life” (p. xiv). She hopes to “ease the journey of other parents who have lost a child prematurely” (p. xv). Using lyrical imagery and specific details, Saad Assel creates a memorable portrait of a unified and courageous family.

When her firstborn son Mazen is ten, kidnappers in Lebanon capture him. Fortunately, they release him quickly (ch. 2, pp. 11-14). When Mazen is nineteen, his father, who smokes, dies of lung cancer (ch. 3, pp. 16-21). Then Mazen takes over the family business of fine china and crystal. But his kidnappers return and demand merchandise (ch. 4 pp. 23-28). Mary Saad Assel decides to send Mazen back to Detroit, where she had grown up, in order to save his life. Friends help Mazen and his mother to reach the seaport of Jounieh, where he boards a ship for the United States. Mary and her two daughters join him a few months later (ch. 5, pp. 30-35).

When Mazen, who also smokes, turns thirty-one, doctors diagnose a terminal and inoperable brain tumor (ch. 6, pp. 44-48; ch. 7, pp. 49-51). Saad Assel fills her paragraphs with metaphors and similes to convey her strong feelings. “The road to recovery would be like climbing a broken ladder, but my soul charged me to travel with the light of hope and give Mazen a set of wings to fly again” (ch. 6, pp. 47-48). Coping with the scary diagnosis, Saad Assel feels as though a “hurricane was running through my body” (ch. 7, p. 49).

Despite the prognosis, Saad Assel hopes for a new cure or longer life span for her son. She urges Mazen to explore natural medicine and to let his faith and mind triumph over his illness (ch. 7, pp. 52-53). Her doctoral thesis concerned neuroscience, and she knows a lot about brain tumors (ch. 8, p. 58). Mazen’s wife Mona also supports her husband’s desire to fight his cancer. They have three young children, and they have been married for seven years.

Mary, Mazen, and Mona consult various doctors about his tumor. One surgeon explains that the brain tumor has spread so much that an operation could damage Mazen’s language centers (57). Soon, Mazen’s headaches become so severe that the family takes him to a hospital. There, the staff gives him frequent morphine shots to ease his pain ch. 8, pp. 57-60).

However, Saad Assel realizes that the morphine can kill her son if administered too often. She concludes that the doctors have “given up on Mazen” and want him “to die peacefully in his sleep rather than to endure the pain of acute headaches.” She convinces a surgeon to operate on Mazen’s brain tumor to relieve his pain. The doctor removes twenty-five percent of the tumor, “leaving vital areas of the brain with minimal injury.” After recovering from the surgery, Mazen receives immunotherapy, which improves his recuperation (ch. 8, pp. 60-67).

But six months later, Mazen’s right arm and leg become weak, and he has trouble walking. Doctors urge Mazen to start radiation. A cousin named Helal administers the radiation, and the tumor stabilizes. Mary urges Mona to get a teaching job to distract her from the tension and anxiety. Saad Assel enrolls in night classes in neuroscience at Wayne State University to understand her son’s ailment better (ch. 9, pp. 68-73).

In 1999, Saad Assel registers to attend the National Brain Tumor Foundation (NBTF) conference in March 2000 in Los Angeles. By early 2000, Mazen’s tumor has grown, he has more trouble walking, and his terrible headaches have returned. A surgeon inserts a shunt to drain excess fluid from the brain. Mazen also does physical and occupational therapy to strengthen his body (ch. 10, pp. 74-75).

Saad Assel’s sister-in-law Amina tells her about a Mexican curandera. Mary and her second husband Ernie decide to see the curandera after the NBTF Conference (ch. 10, p. 77). Mazen has become “[b]edridden, sightless, and inarticulate” (ch. 11, p. 79). Although Saad Assel hopes to find cures at the conference, she realizes that most drugs fail and that the treatments usually focus on people in earlier stages of cancer. Similarly, the visit to a curandera yields a prediction that there is no hope (ch. 11, pp. 81-82; ch. 13, pp. 94-95).

The situation grows bleaker. “A year after radiation and immunotherapy treatment, Mazen had lost balance and muscle strength due to the increased pressure and the new growth in his brain stem. He was unable to speak clearly” (ch. 13, p. 97). At Mona and Saad Assel’s request, Michigan Hospice provides a nurse, a nurse’s aide, a social worker, and physical and occupational therapists. The two women take turns watching Mazen, and other family members also help. Before long, the nurse tells Saad Assel and Mona that Mazen’s organs are failing. His oldest child, who is only six, understands that her father is dying and says goodbye. Mona, Saad Assel, and Mazen’s two sisters stay with him during his last night. At age 33, he has lived for twenty months longer than the doctors had originally predicted. He dies on the morning of Good Friday (ch. 14, pp. 97-98, 100-107; ch. 15 109-110).

After Mazen’s death, Saad Assel remembers all of the details of his Caesarean birth when she was only sixteen. He had to remain in an incubator for a week, and Mazen had an ear infection after Saad Assell brought him home from the hospital at the age of two weeks (ch 16, pp. 116-26). But she returns to the present to mourn her son. The support of her family and friends help her to endure the Moslem funeral and burial (ch. 16, pp. 126-127; ch. 17, pp. 129-135). During the funeral, Saad Assel remembers “the horrifying moments following Mazen’s initial diagnosis” (ch. 17, p. 135). At the cemetery, Saad Assel feels disoriented: “everything solid seemed fragmented, like stones crumbling from towers. The ground seemed uneven, almost moving” (ch. 18, p. 141). She and her daughters scream in grief (ch. 18, 142-143).

During the following months, Saad Assel has more flashbacks to different images of Mazen’s life. She misses him acutely because he was her best friend as well as her son (Epilogue, p. 156). She remembers the painful moment when the neurologist told Mazen, “I’m sorry, but there is nothing else I can do” (ch. 20, p. 151). For a while, she becomes bitter and wishes to die herself in order to reunite with her son. She compares the pain of her separation from him to a razor (ch. 20, pp 151- 153).

To cope with her depression after her son’s death, Saad Assel takes Wellbutrin for three years (ch. 16, p. 136; Epilogue, pp. 164-165). She also goes back to work to distract herself from mourning (ch. 20, pp. 152-53). She has a dream in which her son hugs her and tells her that he loves her (Epilogue, p. 158). She has a vision of Mazen telling her to stay alive to look after his children (Epilogue, p. 162). Eventually, “the hungry beast of death stopped roaring in my head. Mazen was with me in heart and soul. He’d become part of me. I found rest” (ch. 18, p. 143; ch. 20, p. 153). Saad Assel also finds comfort in sharing grief with other parents who have lost children (Epilogue, p. 155) and interacting with her friends, family, and students (Epilogue, p. 163). “It was a struggle, but after acceptance of the unacceptable, I was able to find peace by releasing my emotions, letting go of my anger, and connecting with my inner strength” (Epilogue, p. 159).

This book has some proofreading errors, such as missing articles, transposed words, run-on sentences, subjects and verbs that don’t agree, use of like instead of as, incorrect punctuation, and confusion of past tense and subjunctive verbs.

I highly recommend A Sprinkle of Dust. Saad Assel frankly tells her universal story and reveals the slow, painful process of healing from a great loss. Many readers will find peace and comfort in this moving memoir.

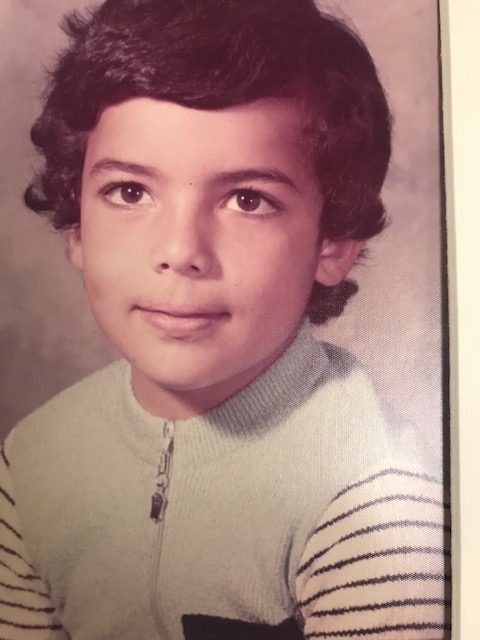

Photo of Mazen, son of author Mary Saad Assel

Janet – Thank you for writing and sharing this valuable piece. You are definitely correct that, in telling of this wrenching personal experience, the grief which is shared among all becomes less difficult to bear.

Thank you, Cousin Marge! I know the author, and she is an amazing woman! Much love! Janet