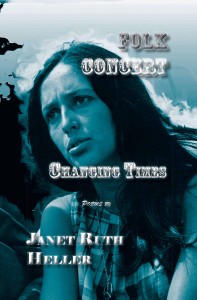

Below is a review of my poetry book Folk Concert: Changing Times.

“In Brief” review of Folk Concert: Changing Times by Kristin Hutchins published in Women’s Studies 41.8 (November 2012): 1010-11.

Heller, Janet Ruth. Folk Concert: Changing Times. Cochran, GA: Anaphora Literary Press, 2012.

In her most recent collection of past and present poems, Folk Concert: Changing Times, Janet Ruth Heller combines the voices she plucks from both different decades and various parts of nature to celebrate both speech and song, especially in times of rebellion. Be it from the mouth of a woman, child, parent, or songbird, these poems are an homage to the discovery and preservation of identity awareness—political, professional, self, social, familial—a knowledge tightly wrapped in Heller’s unmistakably nostalgic prose. Sewn together by uncomplicated rhythm and theme, these poems reveal a subtle, yet rich glimpse into the progression of Heller’s own life, where she exhibits the joys and pains associated with all the steps we take between those before adolescence and those after adulthood. Heller employs simple language—language that is fundamentally folk—which captures in its aforementioned clear-cut rhythm a sound that effectively shows us the allures of activism, on scales either small or large, in the realms of both public and private life.

Several of the poems in this compilation draw from images, experiences, and people Heller has familiarly known. One is never certain where to draw a line between playfulness and frustration, two opposite sensations that Heller skillfully embeds within her work, a knack she masterfully employs, especially in her poems that confront sexism. For example, in “Officemates,” Heller describes the speaker’s first officemate, “Ed” as one who “kept interrupting me/to ask how to spell words/as if I were his secretary/He taught linguistics/and had five dictionaries/on his shelf. After a while/I pretended that I couldn’t spell” (38). This quick flash of spry cleverness presents a unique contrast to the starkly different voice we hear in a poem such as “Obsession,” where the poet repeats images that emphasize a speaker walking this line between opposite sensations, between the brightly wry [end of page 1010] and the bitingly serious. “Obsession” is one of the shortest poems in the book that, by way of its refrain and precision, packs quite the punch. Heller writes: “I walk down the hall at work/and my boss stares at my breasts/… I speak up at a committee meeting/and my boss stares at my breasts/I teach a composition class in front of him/and my boss stares at my breasts/I submit my letter of resignation/and my boss stares at my breasts” (37).

Many of the other poems throughout the book negotiate contrasting points of view, which is apparent in Heller’s ability to distinctively posture her writing as straightforward meditations on gender, love, bigotry, violence, authority, the youth, and education. Interestingly, figures in Folk Concert: Changing Times are seemingly (and mostly) complex female speakers Heller cunningly positions to speak, call, mutter, shout, or sing—making the entire collection, in its unadorned stylishness, read like a love letter to all definitions and conceptualizations of “voice.” For example, poems such as “Traffic Stop in January (For Irving Barat),” “Getting My Mouth Washed Out,” and “Canoe Trip In Northern Wisconsin, 1962” are interconnected through displays of a fifty-three-year-old English professor talking-back to a police officer, a five-year-old arguing with her grandmother, and a group of teenaged summer camp girls singing the song “The Life of a Voyageur” as they boldly paddle their way across choppy waters in stormy weathers. These women, both individually and collectively, are the sharp-tongued, strong-minded, and willfully perseverant woman (/women as a) figure Heller indisputably champions in her work. Much of Heller’s collection lends readers a fresh and contemporary glimpse into the recollections of the flower-child-baby-boom generation, presented by a flower-child-baby-boom author herself, as demonstrated by her own voice that is irrefutably, thematically connected to almost every poem within-here printed. Overall, this slim reserve of folk poetry conclusively contains a verse for everyone, perhaps especially for those interested in Feminism, the anti–Vietnam War movement, political consciousness through social activism, as well as for those interested in nature poems centering on birds.

—Kristin Hutchins